Short selling (often termed “shorting”) is an essential part of being a complete trader. Markets go in both directions. In certain strategies, like spread trades, being able to short sell is a vital ingredient.

Some money managers, such as those operating mutual funds, are not allowed to short sell due to regulatory mandates. On many apps, like Robinhood, you are also not allowed to short sell outside of buying things like inverse ETFs. (Inverse ETFs go up in price when the underlying goes down).

Many traders don’t short sell at all even though they can. It is usually because of concerns over the risk involved or because it doesn’t make much sense relative to their business. For example, Warren Buffett is not a short seller.

Importantly, CFD Trading is an excellent option for aspiring short sellers. They allow traders to speculate on rising and falling prices without taking ownership of the underlying asset. They also offer leveraged trading opportunities, magnifying positions sizes (both risk and reward) with minimal capital outlay.

Some don’t want to short sell because they believe it’s hard making money being short risk premia. In other words, people buy financial assets, like equities and credit, because it’s implicitly understood that over the long-run they will outperform the returns on cash.

This is called a premium, usually expressed as a percentage in extra annual return. Traders and investors expect to be compensated for taking risk.

Therefore, if you are short risk premia it can be hard to make money because over the long-run financial asset markets tend to go up. So many choose to go with the flow and only buy (i.e., be long) financial assets given they expect that they’ll probably make money that way, especially holding long-term.

For example:

Where will Apple stock be 10 years from now? Probably higher.

Where will Google stock be 10 years from now? Probably higher.

If you invest in 10-year US Treasuries, 10 years from now you will very likely have made money by simply holding them the entire time.

Short selling is much more of a short-term trading concept than an investing concept. It’s common for people to “buy and hold” assets over the course of years, but much less common to hold shorts for long durations. Down moves and sell-offs in equity markets tend to be sharper than up moves (“escalator ride up, elevator ride down”) making short selling more of a pure trading concept.

The Mechanics of Short Selling

Short selling involves borrowing an asset that the seller does not own. The short seller borrows the asset from a lender (i.e., a bank, private investor, market making establishment, or whoever may own it) and sells it on the market. When a short position is closed, or “covered”, the seller repurchases the asset on the market, and delivers it to the lender to satisfy the initial amount borrowed.

If the price falls, the short seller makes a profit through this process.

This is because the purchase price was lower than the proceeds of the initial sale.If the price goes up, this process will incur a loss for the short seller because the initial proceeds of the sale are less than the repurchase price.

Naturally, instead of “buy high, sell low” the goal with short selling is to “sell high, buy low”.

Because borrowing is involved in short selling, there is often a fee associated with it, similar to a loan.For example, if certain stocks have high floats (i.e., a large number of shares outstanding) and enough owners of the asset are willing to lend out shares for compensation, short selling will be possible.

For “easy to borrow” shares, the fee is often 1%-2% interest per year.For “hard to borrow” shares, the fee can be exorbitant to the point where it makes short-selling practically off-limits.

As an example, when Tilray stock (NASDAQ: TLRY) was making new all-time highs at breakneck speed in September 2018, the borrowing costs associated with shorting the stock were approximately 1,000%.This had to do with high demand to short it (the stock was in a speculative frenzy) combined with a low float related to its post-IPO lockup (the help ensure that the IPO is successful by reducing the supply of shares in circulation).

Traders who receive interest on the currency balances can also occasionally achieve positive carry on their shorts.If a trader’s base currency offers overnight interest rates above the cost of shorting, this will produce positive carry.

What Markets Short Selling Is Most Common To

Short selling is most common in the stock, currency, and futures markets.

However, when you short sell an asset, your risk is unlimited. If the asset’s value increases, you are forced to buy it back at a higher price, resulting in a loss. Additionally, if the asset’s price continues to rise, you may be subject to a margin call, where you are required to deposit additional funds to cover the losses. Short selling also carries the risk of short squeezes, where other traders buy up the asset, driving up the price and forcing short sellers to cover their positions at a loss. Overall, short selling can be a profitable strategy, but it also carries significant risks that must be carefully managed.

However, when you short an asset, your risk of loss is theoretically unlimited. When you short sell, you can, in effect, lose more than everything. This is because if you short and the asset price more than doubles, you will be out more than 100 percent and will owe money to your broker.

Brokers help to protect themselves against this risk by requiring that traders post margin on their shorts.

The Ethics of Short Selling

Stock Markets

Short selling is nonetheless a controversial topic, especially as it’s applied to shorting equities. A share of stock represents an ownership stake in a company. If the stock goes up, that means the market value of the business is increasing. This is generally positive news for its investors, employees, suppliers, other interested parties, and the broader economy.

Short sellers are often attacked for hoping that businesses will fail because a drop in its price allows them to profit. This can create friction and backlash from policymakers and other parts of society. It’s not entirely uncommon for company management to outright attack short sellers in a company, accuse them of malfeasance, and/or bring litigation against them.

We saw this in part with Enron (even though short sellers were ultimately right). Among high-profile names today, we see Elon Musk attacking short sellers in Tesla stock.

In turbulent financial conditions, regulators may choose to thwart short selling believing it will help calm market dynamics.

This occurred in 2008 when traders piled into short positions against Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns.

However, short selling is an important ingredient to the efficient functioning of financial markets. The ability to short can help tame speculative bubbles (e.g., bitcoin in late-2017) and ensure that price discovery is balanced.

Moreover, short sellers can help to point out genuine problems or malfeasance associated with a company. Oftentimes, it is short sellers – rather than regulators – who discover dubious, illegal, or fraudulent undertakings whether it’s with respect to accounting or other behaviour at companies.

It is also not proven that banning, or at least highly regulating, short selling allows for calmer price action.

Currency Markets

It is also not atypical to see short selling shunned in currency markets, though not to the same extent as in stock markets. For example, in banks in certain countries, it is considered a source of national pride not to short the domestic currency.

George Soros’s short of the British pound in 1992, known as the trade that “broke the Bank of England” also received public backlash. However, traders working for Soros had calculated that the Bank of England didn’t have the reserves available to keep the pound within the European Exchange Mechanism (ERM), a unification precursor to the European Monetary Union, to a rate of 2.7 German marks per pound.

The extra pressure from the short selling had forced the bank’s hand.

In reality, keeping the pound within the ERM was unsustainable given Great Britain’s high inflation rate, which had been officially above 8%.

Ultimately, Great Britain being forced out of the ERM was beneficial as it allowed natural market forces to dictate the exchange rate. Inflation washed out of the British economy and inflation largely hasn’t been a problem in the UK since.

In either case, shorting is not unethical on its own. If short sellers are right, they are simply exposing price inefficiencies in the market.

Alternative Forms of Short Selling

Not all short selling occurs through the process of securities lending. In broad terms, shorting can involve any instrument that a trader can use to profit from a fall in an asset’s price.

Shorting can be accomplished through futures contracts, options (e.g., buying puts), or through swaps. Even though these instruments can be used to short sell, there is no actual delivery of the underlying asset when the transaction is initiated.

How To Short Sell

Many retail traders ask “How do I short the markets?” and the answer is not particularly complex.

On most CFD trading platforms, you will be offered buttons to ‘Buy’ or ‘Sell’ an asset or price. As the button suggests, you can ‘Sell’ most assets – you do not need to have purchased it first.

The costs (or margin) requirements will be roughly the same as a ‘buy’ trade.

The position will behave just as a purchase would, but in reverse. So a falling price will mean the position moves into profit, while a rising price will move the trade into losing territory.

Sometimes a sell order is denoted with a negative ‘per point’ figure. So a short on a currency pair may show -£1 or -$1 for example (Where a buy would show +£1 or +$1 etc).

In order to ‘sell the markets’, a trader is generally looking to take a position against the market as a whole. This could be achieved by shorting an index, such as Nasdaq or the FTSE.

Again, the CFD would work exactly as above, where you ‘sell’ the index and the trade moves into profit if the price falls.

Overview of Short Selling Strategies

Outright Short (Unhedged)

Short selling can be viewed as an outright bet on the fall of a particular asset or security. Some traders may view the fundamentals of a certain market unfavourably and decide to short it accordingly.

Example

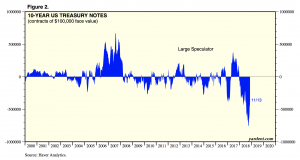

As of November 2018, US Treasury bonds are a heavily shorted market.

The thesis on this idea comes from a variety of different angles.

First, the US Federal Reserve is hiking interest rates and expecting to hike them more than what investors expect based on the forward rate curve.

All financial asset prices are priced partially based on interest rate expectations. Investors fear that this will put too much upward pressure on bond yields.

Additionally, the Fed is tapering its balance sheet of assets accumulated in the aftermath of the 2007-09 financial crisis to help lower yields further along the curve. This means $30 billion per month in Treasuries and $20 billion per month in agency bonds coming onto the market.

On top of that, the US is running an increasing fiscal deficit. This means additional Treasury bonds need to be issued to plug that funding gap. This is more than $100 billion per month.

In terms of basic economics, if supply exceeds demand, price will fall.

Most of the buyers at the margin for Treasuries are foreign central banks. Global reserve growth is approximately flat and foreign central banks are roughly maxed out in terms of how much Treasuries they are willing to buy based on typical allocations. This means that the US is going to have issues finding enough buyers for them.

Traders look at this and view Treasuries as a shorting opportunity. This means they expect prices to go down and yields to go up. (Price and yield share an inverse relationship.)

The risks to the thesis are the negative carry. If you short something with a dividend or coupon, you pay that. In terms of the price dynamics, there is always the risk that private investors pick up the slack in the market if Treasuries look increasingly attractive relative to other asset classes, particularly stocks and commodities.

More technically oriented traders might view things such as momentum, overbought/oversold indicators, support and resistance levels, moving averages, and other such matters to validate a short idea.

A technical analyst might point out the resistance level in the chart below and watch it as a potential area to short.

Hedged Short

Some traders will go short certain securities in order to limit their exposure to the market.

For example, a trader who expects ExxonMobil stock (XOM) to outperform the oil and gas sector may look to go long XOM but short a basket of other oil and gas stocks, like an exchanged traded fund (ETF) like XLE.

Most equity hedge funds are both long and short and usually some mix of 150% long and 85% short.

Many traders do relative value shorts, where they go long one asset and short a similar. They profit if there is a spread expansion in the price.

Traders will also short in order to hedge risk from a specific market factor that they don’t want exposure to.

Example #1

For example, a trader may not want exposure to “momentum” (a type of exposure in factor investing) and hedge out any net momentum-related risk by shorting a basket of assets that represent it.

Example #2

A trader may not want net US dollar exposure, as he would get by being short gold, oil, the euro, and US stocks, and wish to hedge that out. This could be accomplished by going long US dollar futures and measuring out exactly how is needed to be effectively hedged to the movement of the currency.

Example #3

Market makers can develop portfolios that are very skewed to be long or short whatever assets they deal in. If a market maker were to develop a long equities book, he would be inclined to short futures contracts to offset this exposure. This can be done for all other asset classes. For a market maker in fixed income, he may choose to offset the interest rate risk and credit risk profiles of his book through futures contracts as well.

Example #4

Farmers, oil company executives, metals and mining executives, and other individuals in businesses tied to highly volatile commodity prices will often seek to hedge their exposure to the inputs tied most heavily to the success of their businesses.

This can assist in managing the expectations of business earnings.

Example #5

Delta neutrality is often desired by options traders. For instance, if a trader holds long call options and the underlying option has a delta of 0.5 (i.e., the option’s value changes by +/- 0.5 percent for every +/- 1.0 percent shift in the underlying), they will sell twice the shares embedded in the call options. This will hedge the trade against movements in the underlying.

If the trader has bought 100 call option contracts, they are effectively long 10,000 shares of that stock. (Each contract represents 100 shares.) If the option’s delta is 0.5, they will sell 20,000 shares short to fully hedge against price movements in the underlying that may affect the trade’s profit and loss.

Example #6

Some proprietary trading firms will use arbitrage strategies to enhance market efficiency. One way they may do this is through ETFs, which are equity instruments that track a particular basket of assets.

Often, the ETF’s Net Asset Value (NAV) is not in line with the market value of the assets it contains. This creates an opportunity for arbitrageurs. If the ETF’s NAV is trading at a premium, traders may short the ETF and go long the basket of assets it contains, betting that the two will eventually return to equilibrium. If this occurs, they will profit from the rebalancing process. Similarly, if the NAV is trading at a discount, traders may go long the ETF and short sell the basket of assets.

Protecting Against Short Selling Risks

Many traders use a stop-loss when short selling.

This will work to cover, or buy the position back, if the price of the asset rises to a specific level.

This works to avoid the issue of not only a large loss, but also the unlimited potential loss.

Traders must also recognize the potential for what’s called a “short squeeze”.

When traders have a large enough position size, this makes them susceptible to the need to cover in order to limit their losses.

This often occurs through the use of stop-losses or through margin calls.

Others may be forced to cover if the party who had lent the stock wants to sell its shares.

A short squeeze involves the buying of shares and often causes an acceleration in the rise of an asset’s price.

This can cause additional covering in a self-reinforcing way.

Short squeezes can also be caused by investors or corporations directly looking to get short sellers out of their positions.

This is done by buying a relatively large quantity of shares, causing a triggering of stop-losses and margin calls.

The key to avoiding a short squeeze is to watch your position size.

If the prospect of a position moving against you 20%-30% makes you apprehensive, then you are too large.

For institutional investors, the goal is to never become too big of a part of the market.

Conclusion

Short selling is an integral component of being able to freely trade the market.

Financial markets move in both directions and it can be excessively restrictive to limit oneself to being only long the market.