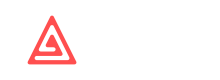

When we think of how to build a stock portfolio, let’s preface this by saying that beating the market is hard.

About 95 percent of professional equity managers won’t be able to beat a representative benchmark over time.This is actually readily apparent after just one year.

This is why passive investing is on the rise.Many simply buy an index fund and call it a day.It’s cheap and simple.If you want to have exposure to stocks, and the odds are so against you picking which ones are going to do better than the market – and which ones will do worse if you short-sell – then why try?

In investing, it’s not whether things turn out good or bad for a company or asset class, but whether they turn out good or bad relative to what’s already discounted in the price.And if you trade tactically, then timing is important, and that’s hard to do.You can also be right about something but get the timing very wrong.

Bettering your reward to risk ratio is a function of achieving balance and avoiding environmental bias.

Each asset class has its own strengths and weaknesses in specific conditions. How can you balance your investment options to optimize your returns over time?

Although you cannot predict which asset or asset class will perform well or poorly in the short or long term, you do know that they perform differently. Adding uncorrelated return streams can increase your returns per unit of risk.

Equities perform well when growth exceeds expectations and inflation is low to moderate. Reserve currency government bonds perform well in times of low growth and inflation. Corporate credit has similar characteristics to equities. Cash performs best when money and credit are tight. Gold and commodities tend to perform well when inflation expectations increase.

Diversification is considered the only free lunch in finance. Proper diversification can increase your reward-to-risk ratio without sacrificing your long-term returns.

When examining the sector breakdown of the S&P 500, which most US equity managers use to compare their performance against, it is heavily skewed towards tech (about 25% of its allocation) and healthcare (about 14%).

S&P 500 sector breakdown:

Please note that these allocations are not static and will change over time.

Because the tech sector has performed well since the financial crisis, with companies like Apple, Google, and Facebook replacing GE, ExxonMobil, and Walmart as the world’s most valuable public companies, the US market has outperformed. Europe, on the other hand, has largely lagged behind US returns due to its low exposure to the tech sector. (European stock indices have around 5 percent exposure to tech.)

Since the financial crisis, the weight of financials has decreased and this sector has deleveraged. Therefore, the S&P 500’s allocation toward financials is lower than what we see in most other markets.

When we think about how to achieve balance in equities, we should consider weighting assets like utilities higher than 3-4 percent each because of their sensitivity to interest rates. This gives them a behavior that’s often unique relative to other sectors. Energy, materials, real estate, and utilities combined only make up 12-13 percent of the S&P 500.

Moreover, utilities have a more bond-like character. Regardless of the state of the economy, people still need to pay their water, gas, and electric bills. This makes their cash flow more stable relative to cyclical sectors like tech, energy, and consumer discretionary.

Consumer staples, at about 7 percent, are also more stable compared to the market. These are products that companies sell that are always in demand – like food and everyday items – and are not as vulnerable to being cut out of a budget when the economy turns down, unlike the latest electronic gadgets, luxury items, vacation cruises, and other gaming, lodging, and leisure products.

How to build a stock portfolio – achieving better balance

Investors who want equity-like returns but with some extra safety often seek dividend stocks and “defensive” stocks, such as utilities and low price-to-earnings stocks with positive cash flows.

Tactical traders often want to own cyclicals toward the beginning of the cycle (e.g., tech, consumer discretionary, autos, equipment), and shift more into utilities, staples, or even healthcare as the cycle progresses.

Some might view something like healthcare as more secular than cyclical because of aging populations, though it’s dependent on political winds.

Investors often look toward dividend stocks because the size of the dividend effectively implies that a certain amount of earnings are more or less “guaranteed” each quarter.

But, of course, there are a ton of different things that can impact the health of a business. Even for mature corporations selling products with stable non-seasonal demand, they will inevitably see quarterly earnings underperforming the dividend at some point. This can also increase the odds that the dividend will be cut if it can’t be sustained at its current level. The stock is generally badly punished whenever a dividend is cut because it signals a broader warning over the company’s financial health.

Defensive stocks are often commonly thought of as stocks with a relatively low US market correlation and low drawdowns relative to the market.

The energy sector is less correlated to the overall market than average and tends to have higher than average dividends. But oil and gas companies normally use a lot of leverage because they are capital intensive. And they are tied heavily to the performance of energy commodity markets. The oil market is about twice as volatile as the US stock market and is prone to painful trending down moves.

This makes the oil sector more vulnerable than average to large drawdowns.

Any companies whose cash flow is heavily tied to the price of a singular or limited set of commodities is at risk.

Being overly concentrated in a certain sector or two can be dangerous because the source of the cash flow isn’t well diversified relative to how it might be within a representative index.

In 2000, tech crashed due to excessive optimism over the future prospects of internet and tech companies.

In 2008, financials crashed due to overleverage in the banking sector, mostly related to excessively risky lending in the residential housing markets.

In 2015-16, oil and gas stocks drew down because of the crash in the crude oil market due to a supply overhang.

You don’t want to be too dependent on a certain type of cash flow.

The data below run from January 1999 to February 2020:

General findings

Note that staples and utilities have the lowest correlation to the market. They are less cyclical because their cash flows are more stable.

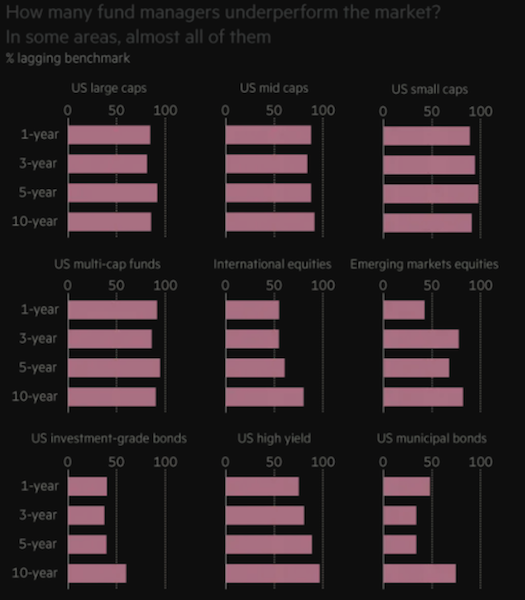

We also know that we want to have the appropriate balance to growth and value to build a better equities portfolio in risk-adjusted terms rather than having a bias of one theme or factor over the other.

Notice how the general market outperforms (portfolio 1 below) both a “value” portfolio (portfolio 2) and a “growth” portfolio (portfolio 3).

Portfolio allocations

Portfolio results

General points

So far, we can probably take away the following points:

1. We can increase our reward to risk by balancing our sector weights in a more efficient way.

We can limit our concentration to more cyclical forms of cash flow and increase our weights to sectors that produce more stable cash flow.

2. To balance our risks better, we should weight more heavily toward sectors that are less correlated to the market and toward sectors that have lower beta to the market.

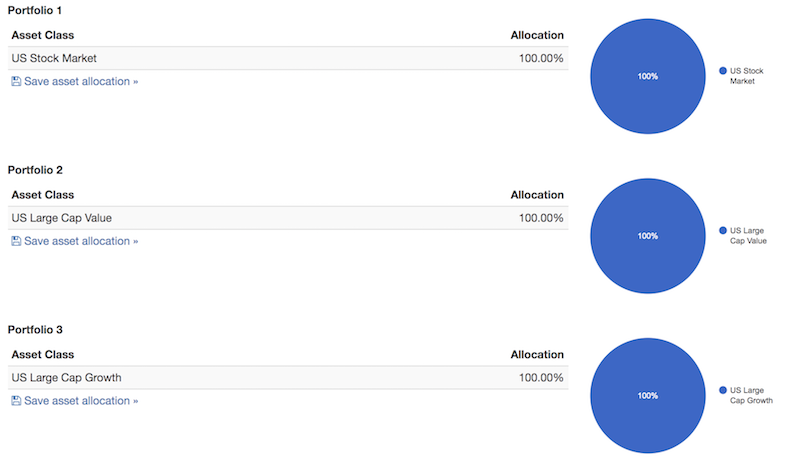

A study by the asset management firm AQR found that the lowest beta parts of the market tend to have higher risk-adjusted returns than the highest beta components.

The green dots in the image show risk-adjusted return.

The 1931 to 2011 period (left image above) shows superior risk-adjusted returns in the lowest beta equities.From 2011 to the present (right image), this relationship has become even more pronounced with the lowest beta stocks outperforming their higher beta peers.The 2011-2019 period, of course, was also characterized by a relatively steady bull run.

This means we should probably overweight lower beta sectors like utilities and staples relative to high beta, cyclical sectors like consumer discretionary and industrials.

3. We should strive to have a healthy balance between value and growth.Though tech is cyclical and has high drawdowns when people concentrate their bets in this sector, it is an important growth leg and source of balance in a portfolio.

4. We should also balance to a degree based on market capitalization or size.

A portfolio that’s split between small caps (i.e., Russell 2000), large caps (i.e., Dow Jones Industrial Average), and the NASDAQ (i.e., a tech-/growth-focused index) in equivalent parts improves the reward relative to the risk in comparison to the S&P 500.

Example allocation of a balanced equities portfolio

If we’re looking for a stock allocation that’s better balanced throughout the economic cycle and not too dependent on idiosyncratic cycles (e.g., tech, oil and gas, mining), here’s one that improves our reward relative to our risk over the S&P 500:

| Ticker | Name | Allocation |

|---|---|---|

| XLY | Consumer Discret Sel Sect SPDR ETF | 5.00% |

| XLP | Consumer Staples Select Sector SPDR ETF | 19.00% |

| XLE | Energy Select Sector SPDR ETF | 5.00% |

| XLF | Financial Select Sector SPDR ETF | 6.00% |

| XLV | Health Care Select Sector SPDR ETF | 8.00% |

| XLI | Industrial Select Sector SPDR ETF | 4.00% |

| XLB | Materials Select Sector SPDR ETF | 4.00% |

| XLK | Technology Select Sector SPDR ETF | 16.00% |

| XLU | Utilities Select Sector SPDR ETF | 23.00% |

| IWM | iShares Russell 2000 ETF | 10.00% |

We can see below that the portfolios mirror each other – after all, they are the same asset class – but the blue line (“balanced”) outperforms the pre-packaged version (S&P 500).

Slowly over time it produces better returns with less risk.

Portfolio Returns

| Portfolio | Initial Balance | Final Balance | CAGR | Stdev | Best Year | Worst Year | Max.Drawdown | Sharpe Ratio | Sortino Ratio | US Mkt Corr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced | $10,000 | $37,551 | 7.15% | 12.80% | 29.37% | -31.63% | -43.91% | 0.49 | 0.69 | 0.97 |

| S&P 500 | $10,000 | $32,511 | 6.34% | 14.41% | 32.31% | -36.81% | -50.80% | 0.40 | 0.56 | 1.00 |

Differences in Exposures

Here we can observe the differences in exposures between the two among various market capitalizations, sectors and themes:

| Style Category | Balanced Portfolio | S&P 500 |

|---|---|---|

| Large-cap Value | 25.19% | 46.22% |

| Large-cap Growth | 48.40% | 52.83% |

| Mid-cap Value | 9.92% | 0.00% |

| Mid-cap Growth | 0.00% | 0.55% |

| Small-cap Value | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Small-cap Growth | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Global ex-US Developed Markets | 0.86% | 0.00% |

| Emerging Markets | 0.00% | 0.05% |

| REITs | 2.91% | 0.00% |

| Corporate Bonds | 0.00% | 0.36% |

| Long-Term Treasuries | 5.09% | 0.00% |

| Intermediate-Term Treasuries | 6.46% | 0.00% |

| Short-Term Treasuries | 1.16% | 0.00% |

| R Squared | 95.14% | 99.90% |

Balanced portfolio sector exposure

S&P 500 sector exposure

Rolling Returns

We can also see that if we look at our rolling returns, or the average annualized returns over various timeframes, the balanced portfolio is an improvement over the S&P 500.

It achieves higher returns and has lower drawdowns.

| Roll Period | Balanced Portfolio | S&P 500 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | High | Low | Average | High | Low | |

| 1 year | 9.05% | 29.37% | -31.63% | 8.49% | 32.31% | -36.81% |

| 3 years | 8.85% | 18.61% | -4.14% | 8.02% | 20.31% | -8.36% |

| 5 years | 8.79% | 16.85% | 1.53% | 7.80% | 17.85% | -2.23% |

| 7 years | 8.70% | 14.24% | 1.01% | 7.63% | 14.70% | -1.53% |

| 10 years | 8.62% | 12.94% | 3.26% | 7.53% | 13.44% | 1.42% |

| 15 years | 8.67% | 10.89% | 6.19% | 7.60% | 9.82% | 4.97% |

(More information on portfolio statistics can be found in the Appendix at the bottom of this article.)

Conclusion

When thinking of how to build a stock portfolio, the default construction (the S&P 500) is a notoriously hard benchmark for investors to beat over the long-term.

With the role of trading costs (slippage, commissions, margin fees) and proper liquidity management, adding value to the markets is not an easy thing to do.

However, we can make improvements to the allocation to be better balanced to various sectors and market capitalizations (large cap, mid cap, small cap) to improve our reward relative to our risk.

That doesn’t come without drawbacks. For an individual investor, better optimization of a portfolio requires measurement, management, and additional complexity in general. Trading and investing is a full-time job.

Moreover, the S&P 500 – as well as the NASDAQ, Russell 2000, Dow Jones, and emerging markets – have their own liquid futures markets. So, gaining a certain level of leveraged exposure to the stock market might fit the needs of certain traders and investors better. In those cases, it’s often simply the best option to invest in a pre-packaged version of the stock market.

Indexes also provide the buyer the benefit of survivorship bias. Only 10 percent of the companies that were in the Fortune 500 in 1955 still remain. Picking which companies are going to be good over the long-run is a difficult exercise. In the indexes, companies that perform well and meet certain criteria will be added while poor-performing companies will be dropped.

This is all automatically done for you, whereas when to get in and out while investing in individual companies is up to your discretion.

The ones that do succeed tend to eventually decline and be replaced by entirely new types of businesses. Thirty years ago, we could have never anticipated that today’s big companies would be related to shopping on a computer (Amazon), finding information on a computer (Google), social networking on a computer (Facebook), electronic all-in-one “smart” devices (Apple), and software, hardware, and data storage (Microsoft). They’re related to technologies that didn’t exist in the recent past yet have created enormous amounts of value to consumers and advertisers. The landscape will look a bit different after another thirty years. Predicting what these technologies and types of businesses will be is not easy, and particularly which companies will become the next global stalwarts.

Getting a more balanced allocation requires investments into individual equities or ETFs that provide broad exposure. This involves trading costs and most ETFs still have fees that eat into returns. That can be another argument for sticking with passive index investing.

Even when we have better optimized exposure to the equities market (or US equities, as we mostly focused on within this article), we still need to position that within the context of a portfolio that’s balanced more broadly via fixed income, commodities, gold/metals, real and alternative assets (real estate, hardwood, private equity, specialty lending, venture), and different currencies.

That’s why we recommend learning how to achieve strategic diversification and to build a balanced portfolio that can perform well in different environments.

Appendix

Portfolio Assets

| Ticker | Name of instrument | CAGR | Stdev | Best Year | Worst Year | Max.

We see such advantages as:

|

|---|